Testimonies:

Francois Matata

Jeremy Ngilaluko

Patrick Nontumpo

Nkembo Simanzondo

Feza Mukankuranga

Flora Amina

Lula Malundama

These oral testimonies were collected by researcher Joe-Yves Salankang Sa-Ngol via a Whatsapp voice note chain. Contributors were invited to speak about their experiences with and relationships to the mines in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

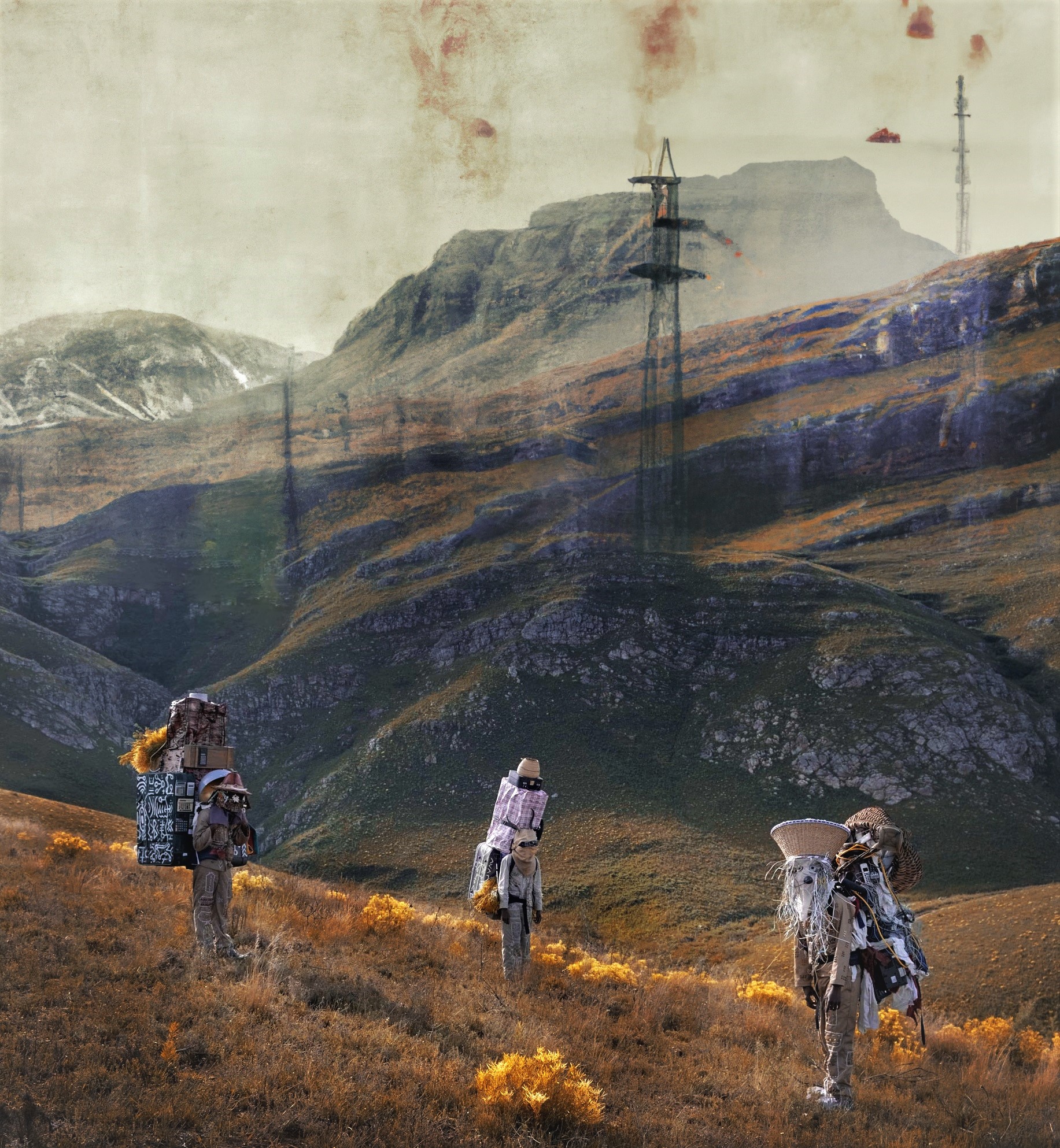

JoeYves Salankang Sa-Ngol : All the protagonists are Congolese, living in South Africa. We retained them after a voluntary call to testify. Indeed, our commitment as a volunteer within the Congolese community has enabled us to build a certain relationship of trust with an important number in our community; which allowed us to easily spot them but also to put in confidence those who accepted to testify. And for such a sensitive subject, it must be recognized that several people have admitted having things to say but prefer silence: - some because they fear that their security will be compromised; - others just because it is painful episodes that they prefer to forget rather than stir them up. In this mosaic of confidential testimonies, some are direct survivors of the landslides, others witness to the suffering and ordeal of this exploitation and still others have indirectly suffered for having lost loved ones. These testimonies also speak of the damage deliberately caused to the environment by mining companies. All the protagonists have in common the fact that they come from poor backgrounds and live with a permanent feeling of revolt to see the resources of their soil becoming a sort of curse for them. All the protagonists live with a permanent regret at having seen themselves obliged to immigrate very far from their lands, in search of a better life.

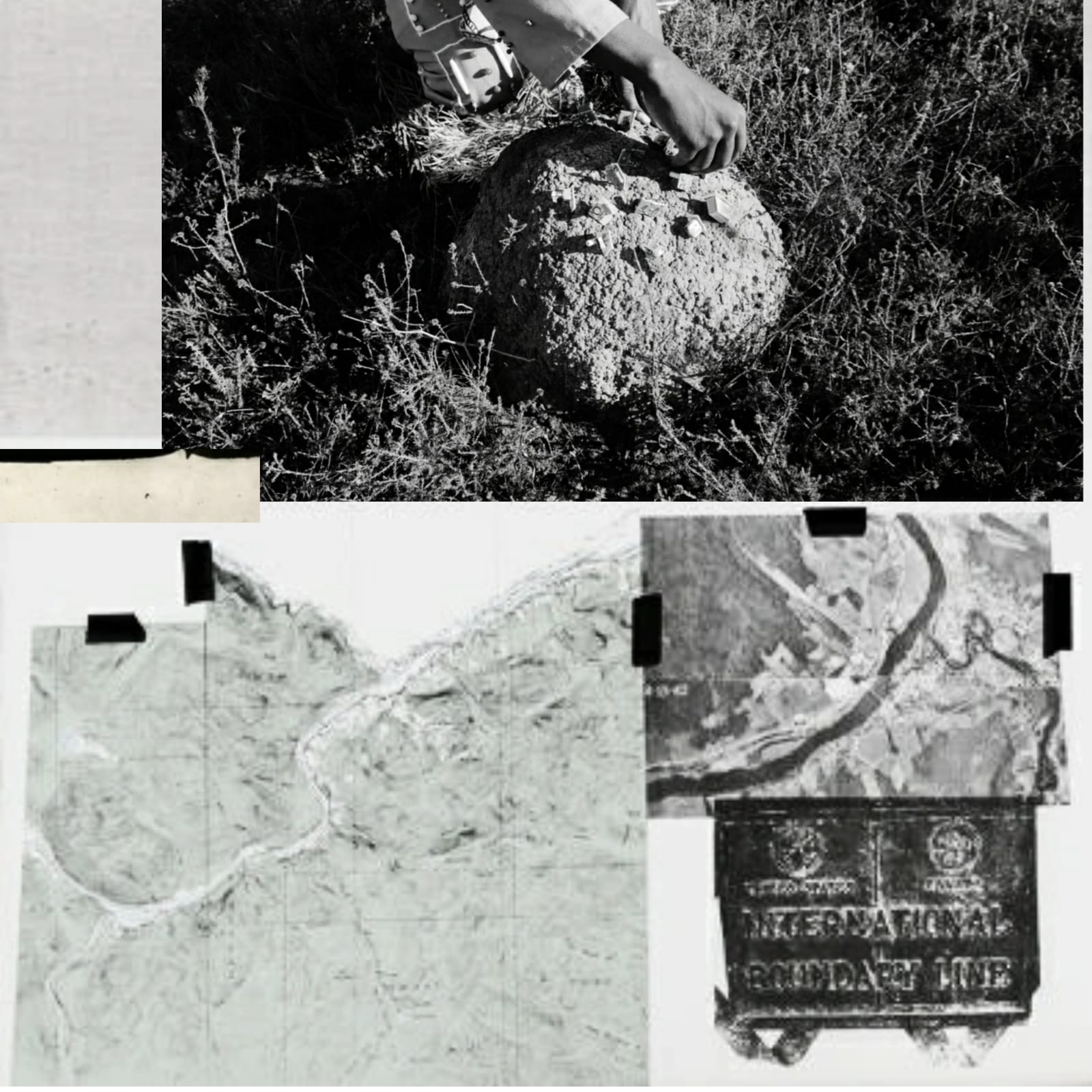

Hiroshima Aerial View

︎