︎

By extending this research to South Africa, we began to look at the story of uranium in the country and its shrouded nuclear history. On the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, uranium was found in the same rock as gold. (Both my father and grandfather worked in the Harmony Gold Mine in the Free State, South Africa, and this became a point of personal interest for me, having photographs and personal histories to work through). For a long time, the mining companies owned the gold but the state owned the uranium. Testimonies have shown that miners could be mining uranium their whole lives and not be aware of the radiation they were being exposed to.

Uranium became an important material in the apartheid government’s quest for international leverage, and a sophisticated nuclear programme was developed – of which only a limited archive of evidence exists today. Our research into nuclearity showed that colonialism remained central to the nuclear order’s technological and geopolitical success. And a key question in this project was, inspired by Gabrielle Hecht: what constitutes a nuclear place? And, following from that, how do we bring the African continent into the discourse surrounding nuclearity and technological progress?

The central image of the atomic bomb, and these questions about nuclearity, give rise to larger questions about technology in the world like: is there an order beyond the binary of the technologically advanced, industrialised ‘centre’ and the raw materials-producing ‘periphery’. We created two works which we call ‘mapping interventions’. When we searched on Google earth for streetviews of Shinkolobwe or Vastrap (the site in the Kalahari desert of South Africa where satellites captured imagery of ‘potential’ nuclear weapons testing taking place), we found nothing. It was as if these two historical sites did not exist. At Shinkolobwe, the Belgian government filled shafts with concrete to prevent future access.

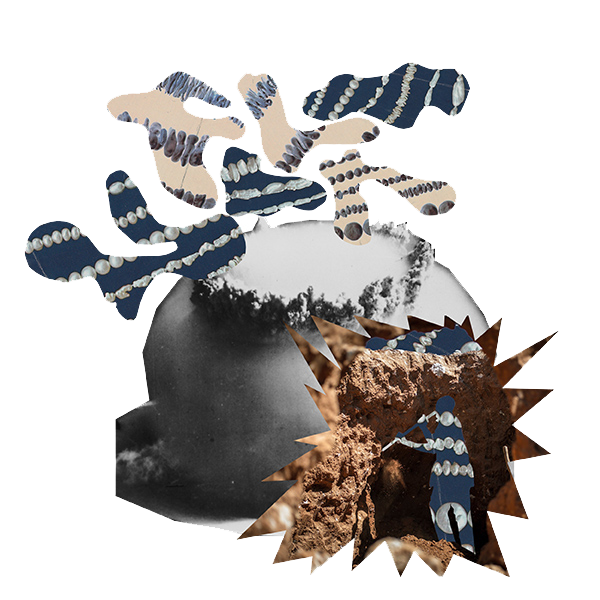

In the Kalahari desert, the South African government ordered the shafts of the nuclear testing site ‘Vastrap’ to be sealed by the pouring of concrete into steel drums. We created a 360 degree ‘portrait’ for each of these places – a collaged visual layering of narratives that are usually kept distinct and a fashioning of new historical constellations. We wanted to problematize and disrupt the disembodied, satellite-like vantage point from which locations are usually viewed on Google Earth – in these portraits, there is no clean horizon: you are inside of the environment; time and perspective are warped. This way of seeing acts as a kind of resistance to the violent dislocation and displacement of images and materials, and their subsequent circulation.

Laager.

Noun. HISTORICAL•SOUTH AFRICAN: an encampment formed by a circle of wagons.

2. an entrenched position or viewpoint that is defended against opponents.

"an educational laager, isolated from the outside world"

Verb. HISTORICAL•SOUTH AFRICAN

- form (vehicles) into a laager. For example: "Van Rensburg's wagons were not laagered, but scattered about"

︎